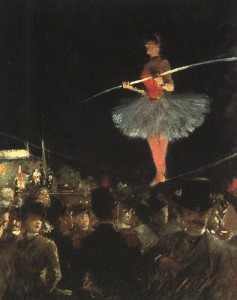

I often think of the act of creating great art as a balancing of universal and particular elements within a work. The artist must walk a tightrope, to borrow an idea from Juliette Aristides; his balancing act is between two extremes, but in order to keep his balance he  must distribute his weight into both extremes (hence tight rope walkers hold the long pole to keep their balance). They must extend their weight into the extremes, in the case of the artist, he must present his subject in universal and particular terms. I cannot think of another artist who understands this concept better than Shakespeare. His character Theseus, speaking to Hippolyta, says that “the lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact.” It is incredible to hear Shakespeare talk of “the poet” in broad terms, and in some removed and qualified way, he seems to be speaking of himself in his own role as poet. The poet’s act of creation is a stretching out into the realm of heaven and earth (universal and particular):

must distribute his weight into both extremes (hence tight rope walkers hold the long pole to keep their balance). They must extend their weight into the extremes, in the case of the artist, he must present his subject in universal and particular terms. I cannot think of another artist who understands this concept better than Shakespeare. His character Theseus, speaking to Hippolyta, says that “the lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact.” It is incredible to hear Shakespeare talk of “the poet” in broad terms, and in some removed and qualified way, he seems to be speaking of himself in his own role as poet. The poet’s act of creation is a stretching out into the realm of heaven and earth (universal and particular):

The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

It is the same of the artist making great works. He must body forth his imagination, put into some particular form a universal ideal, those two must intermingle and mix together in order to create the greatest art. There is something immaterial that Shakespeare gets at to, the “airy nothing” must occupy a “local habitation and a name.”

Here is the rest of the speech:

THESEUS

More strange than true: I never may believe

These antique fables, nor these fairy toys.

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact:

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold,

That is, the madman: the lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen’s beauty in a brow of Egypt:

The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear!